Subsystem XIV Search

<- home

The core idea of searching the database: every listing of database objects (CECase, Person, Property, etc.) is built using a SQL query that’s assembled based on the configuration of a passed in SearchParams subclass, such as SearchParamsCEActionRequests.

SearchParams objects store various search parameter values that are injected into SELECT statements and switches that turn each one on and off.

To use the search utility:

- Call the appropriate factory method on the

SearchCoordinatorfor the defaultSearchParamssubclass you want, such asgetDefaultSearchParamsCEActionRequests(). This will usually happen by a backing bean or perhaps even the domain coordinator. - Customize the default configuration of the

SearchParamsobject you get back. - Usually this will be used on page load to build a starting list for display

- Wire the backing bean properties to the various parameters on your search object so the user can tinker with them

- Use the

SearchParamsobject to shuttle revisions on the initial query to the integrator.

Case study: Creating a Violation search utility

This case study will enact the steps required to build a search tool for the Violation objects directly. As of this writing, search object sub-families exist for code enforcement cases through a query of CECase objects. Clients need to demonstrate value and the primary means of doing so is violation compliance metrics. Querying cases and then extracting their Violations in Java is sub-optimal, since we’ll probably miss violations that still exist on cases that don’t get pulled up in our case queries.

Actors involved in searching

SearchCoordinator

Responsible for initializing all Queries and their parameters, as well managing the actual execution of Queries against the database, the SearchCoordinator’s methods will form the basis for our build out.

SearchParams subclasses

These folks store the actual switches used by our integration classes for writing SQL to shoot down to the database.

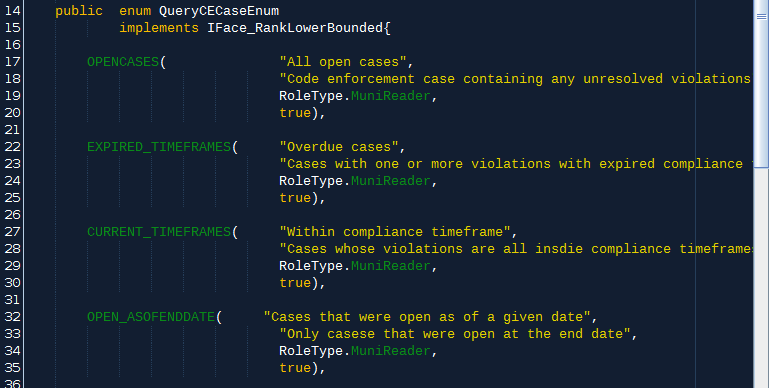

QueryXXXEnum family

Queries of an object such as Person or CECase are configured using rules attached to enum values stored in each search pathway’s governing QueryXXXEnum class.

This clip of the top of our QueryCECaseEnum class will be our template for QueryViolationEnum:

QueryXXX

Our primary aggregation object of these search-related classes is the QueryXXX class, all subclasses of Query. They all contain an identifying enum value, a List of SearchParamXXX objects, and the actual bob result list assembled by our clunky and finicky (by oh so faithful) integrators.

Step 1: Build QueryCodeViolation

Using QueryCECaseEnum as a template, let’s create a QueryCodeViolation which we’ll use to store all of our related objects.

A refactor copy operation in NetBeans allows a smooth templating.

The key task here is to modify the member variable types to match our CodeViolation related sublcasses. We’ll build those objects as we do this so our type-checking system can watch our six.

Step 1A: Creating QueryCodeViolationEnum

Refactored version of QueryCECaseEnum. We’ll review those members in a moment; for now, we just need to class to exist to modify our QueryViolation.

Step 1B: Creating SearchParamsCodeViolation

The second member of QueryCodeViolation is a List<SearchParamsCodeViolation>. We adapted SearchParamsCECase to create this new subclass of SearchParms.

This is a list because a given query might require building and running a few separate SELECT statements against the database. For example, we might want a list of violations that were created OR cited during a period. Since we’ll be building the SQL statement programatically, it’s often easier to just “do the union manually” by adding the results of two SELECT calls to the same list.

So: one instance of SearchParamsCodeViolation means a single SELECT execution, and a single call to the SearchCoordinator’s runQuery method.

Step 1C: Configure Business Object list

The third member of QueryCodeViolation is a List<CodeViolation> allowing our query object to hold the actual business objects that were returned when each of our parameter objects is run against the db.

Step 2: Rough in methods on SearchCoordinator

Now that we have actual QueryCodeViolation objects, duplicate and refactor the applicable CECase related methods to work with QueryCodeViolations. Our families of methods on SearchCoordinator work together to build and execute queries against the db, in source order:

BuildQueryXXXListmethods: requires the user’sCredentialand uses the permission settings on that as well as those attached to eachQueryXXXEnumto assemble a list ofQueryobjects for a particular business object ready to be customized and sent back to theSearchCoordinatorfor execution. These suckers do this by callinginitParamsinside a for loop over the enum values.genParams_XXX_YYYprivate methods: Primary logic holders of search operations, these puppies are responsible for assembling a singleSearchParamsXXXsubclass with switches set properly to answer a business question. These are called bybuildQueryXXXmethods internally based on the triggeredcase.initQueryoverrides: logic container for callinggenParamsXXXfor the triggered enum instance.runQueryoverrides: What we’ve all been waiting for: the true site of query execution coordination. Calls relevant methods on object integration classes who talk to the db.

Step 3: Write searchForCodeViolations method on integrator

The CaseIntegrator will actually build SQL for us inside an elite method of our integrator requiring a single SearchParamsCodeViolation instance which it will unpack in some multi-layered logic to build a valid SQL statement

As usual with our business objects, we’ll often get back just an ID list that will need to be built into an actual BOb later by the coordinator who makes sure all the business rules are followed.

Use public List<Integer> searchForCECases(SearchParamsCECase params) for a template.

Iteratively build our SQL and search params

We’re ready to get to the guts of the database query. Since we’re building the SQL programatically, we’ll create member variables on SearchParamsCodeViolation to plug into our cascade of logic turning on and off various components of the SELECT and creating injection points for values the user wants to use for restricting results.

Note that all queries share utility methods for configuring proper SQL syntax for date range queries and extracting keys from core objects, such as User and Credential.

We’ll rougly have member variables on our SearchParamsCodeViolation object that correspond to the database fields, taking joins into account to allow querying across tables.

Note the SearchParams superclass

SearchParamsCodeViolation’s’ parent will manage most of cross applicable field switch holding, such as municipality control, date and user containers, and some schnazzy date utility switches that automatically convert a relative date (34 days ago) into an actual date threshold to use in generating the SQL clause.

Set #4 in the SearchParmas parent is a data restriction facility in which a user can be required to have a certain role to even execute that particular configuration of query switches. Our SearchCoordinator will ensure that these rules get followed by forcing query requests against all tables in the system get routed through the type and call pathways which will reject malformed parameters before they hit the integrator. No logic or access restriction logic lives in interators!

Building date and user fields enums

To allow user customized queries, and easy programmatic tweaking of SQL that can be type checked at runtime, the relevant date fields on the DB table map to Java enum values in theSearchParamsCodeViolationDateFieldsEnum and the relevant user fields in the SearchParamsCodeViolationUserFieldsEnum class. Each enum value has two members: a human friendly title and the specific database field name. The integrator method we’re writing will use these enum member values to write valid SQL to throw against the DB.

Generation note: since codeviolation is a first generation db table, it doesn’t conform to the date and user field standard implemented by the humanization database process described elsewhere. This means future tables should be built such that a shared set of date and user field enums can be used (and extended) which will reduce query logic failures and syntax bugs.